I Didn’t Want to Push My Aunt to Get the Vaccine. Now I Live With Regrets

In normal times, the ICU is a dreadful place.

Sickness lingers like a fog. You can feel it, sense it, even hear it—the machinery pumping, the alarms ringing, the nurses scrambling.

In pandemic times, the ICU is chilling. Death lives here.

Medical staff members wear green biohazard suits, face shields, latex gloves and shoe coverings. Strips of red tape—“ISOLATION,” they read—mark the windows and doors of individual rooms.

Behind each is a patient who cannot breathe on their own, kept alive by a ventilation machine that is connected to an invasive tube running down their windpipe and into the lungs. Each room is almost identical: a person, some on their stomachs and others on their backs, sedated and paralyzed, roughly a dozen patches and pipes protruding from them, blankets hiding their naked bodies.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Most of them will not make it out of here, the nurse tells me. In fact, at this particular ICU on the Southern Gulf Coast, COVID-19 patients needing a ventilator have a fatality rate approaching 100%. Over the last year, hundreds of them spent time here. Seven of them survived.

“I wish people could walk in my shoes for a day,” the nurse muffles through a mask.

The nurse is nice, but blunt. She’s frustrated like so many in the medical community, she says. In this ICU, there are 25 patients battling COVID-19. She pauses before finishing the thought: 24 of them are unvaccinated.

That includes the patient before her, the one with braided red curls, pale skin, the one with rosaries draped over her bedside, lying flat on her stomach, her left ear and cheek exposed, a tube inserted in her mouth filling her lungs with oxygen.

She is in her 40s, a mother to a teenager. A wife to a husband. A daughter to an 81-year old mom. A sister to three older siblings. A friend to hundreds.

And an aunt, a godmother and a kindred spirit to one lucky nephew.

Me.

‘A small, painless shot in the arm’

Normally, I write about college football for Sports Illustrated. As the son of a longtime high school football coach, I’ve always been passionate about sports. My stories usually include words like touchdown, field goal and kickoff—not ICU, illness and death.

This isn’t a story about a vaccine. It isn’t a story about a virus. And it isn’t a story about one single person. It is a story about them all.

It’s a sad story, like so many in this Godforsaken world today. We are surrounded by sadness. We are surrounded by sickness. These stories are playing out across our stubborn country, throughout our ailing world. There are thousands of them and this is but one.

It ends in suffering. It ends in the most awful, debilitating pain a human can stand.

Some people believe they know what happens when we die. Heaven, hell, purgatory. The truth is, no one really knows. What we do know about death is what it does to those living. It is crushing. We know that. And this, this is crushing.

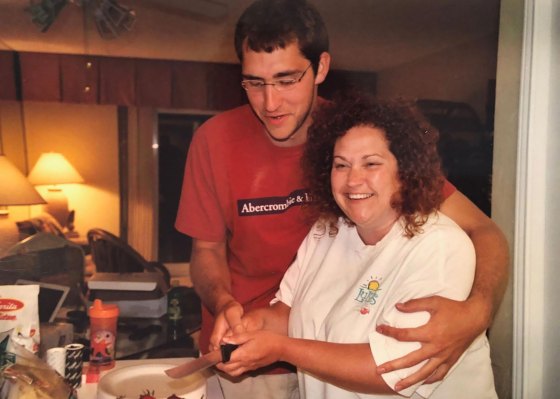

No one was quite like my aunt. And I do mean no one.

How do you describe someone who could make you both laugh and cry in the same sentence? A woman who devoted her life to helping underprivileged young people with special needs?

Do you know the famous Jim Valvano speech? At the 1993 ESPY Awards, the former college basketball coach, then sick and dying of cancer, told millions the secret to life: If you laugh, think and cry every single day, you’ve lived, he said.

My aunt embodied that. A laugher, a thinker, a cryer—truly the life of every party. She gave and she gave. No one showered me with more adoration than her.

We were only separated by 11 years. When she was 18, I was 7, and she introduced me to animated Disney movies. Aladdin, The Little Mermaid, The Lion King. We’d slide the old VHS tapes into the VCR and settle in for a fun 90 minutes.

When she was 25, I was 14, and she’d assure me that the bullies at school were nothing but big dummies.

And when she was 48, I was 37, and I assured her that a small, painless shot in the arm would protect her.

I never wanted to be too pushy about it—and now, boy, do I regret that—but each time I saw her over the last six months, I reminded her that the tiny jab could prevent serious illness or death.

She refused. They don’t know the long-term effects, she said. You’re right, I told her, but we do know the effects of COVID-19: sickness, hospitalization, death.

Her brother pleaded with her, too. Always a jokester, he poked at her about it. “If you ever get hospitalized with the virus,” he told her, “I hope you make it out so I can tell you, ‘Told you so.’”

Saying goodbye in the ICU

Across the U.S., health agencies are reporting some 150,00 new COVID-19 cases a day, the highest rate since last winter, according to Johns Hopkins University numbers. Hospitalizations are likewise approaching the previous the high point of the pandemic, with many facilities across the nation again running out of beds and on the cusp of rationing care. As of writing, the seven-day average of daily COVID-19-related deaths is approaching 1,550.

There is, of course, protection for those over 12: the authorized vaccines. The latest data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, published Sept. 10, found that unvaccinated people were over 10 times more likely to be hospitalized than vaccinated people, and about five times more likely to be infected. Despite that data, some 37.5% of people in this country currently eligible for the COVID-19 vaccines are not vaccinated.

My family is a true case study to help understand this trend. During a family vacation to the beach in late July, nine adults stayed in a condominium. Seven were vaccinated. Three of the nine later tested positive for COVID-19. Two, both vaccinated, felt mild cold symptoms. A week later, the unvaccinated third was hospitalized.

Fourteen days passed from the time of my aunt’s positive test to the day they wheeled her into ICU, sedated her and intubated her by inserting a tube into her lungs. In the days leading up to that point, she was perfectly alert, laboring to breathe but with the ability to text from her hospital bed.

Along the way we exchanged messages. I asked her if she needed me to travel to the hospital with a bike pump and fill those lungs of hers with air. “I think that would help,” she jokingly wrote back. I sent flowers, a card and chocolates a day before they moved her into ICU. While eating the chocolates, she texted me a thank you note. She really got a kick out of the card, which I wrote with inspiration from a TV show we both loved: Seinfeld.

A music lover, she complained that there were no “good vibes” in the ICU (eventually, we set up a transistor radio for her, and it played and played while she lay sedated).

A few days later, hours before intubation, I sent her another text, this one more serious. There’s no room for it all here. And I’m not sure I’ll ever reveal its full contents. But I told her that she means more to me than just about anyone on this Earth and that I am the man I am today partly because of who she is. It rubbed off on me, I texted.

In that note, I briefly mentioned that tiny little shot. I was experiencing conflicting emotions, I wrote to her. I was sad and I was also angry – “and you know why,” I texted.

Finally, I told her to fight. Fight hard. And when you get out of there, I wrote, your family will be waiting.

She never responded to that text. I’d like to believe she read it and that she went into sedation knowing what she meant to me.

In reality, I’ll never know.

Exactly two weeks later, I walked into the ICU to say goodbye.

For a fleeting moment, it was just me and her, and that transistor radio, which sent tunes dancing across the room: Let’s dance in style. Let’s dance for a while. Heaven can wait. We’re only watching the skies.

She had been positioned on her back so family members could sob over her lifeless body. She was attached to a dozen machines, on the precipice of death, completely sedated and paralyzed. Her chest rose and fell with the ventilator’s hum.

It was the last time I saw her alive.